"Cheap, Snarky, Sly," And A Hypocrite

Part 2 of Stuart Stevens' "Pink Mafia" series on the GOP's secret gay powerbrokers.

Read Part 1 in the series Pink Mafia: The Hidden Power Structure of Closeted Gay Men in the Republican Party

Before Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law and its many variations in other states, there was a series of legislative initiatives pushed by the Moral Majority following the 1980 election of Ronald Reagan. The first to hit the floor of the House of Representatives in the 1979-1980 96th Congress was H.R.7445 – “A bill to strengthen the American family and promote the virtues of family life through education, tax assistance, and related measures.”

The bill was a long laundry list of legislative actions that the sponsors believed would use the power of government to promote “conservative” family values. Like Governor DeSantis’ legislation decades later, the focus was on education, which was seen as a morally corrupting influence on impressionable youth. The Congressional Record summarized:

The bill amends the General Education Provisions Act to prohibit payments under such Act to States or State or local educational agencies, which: (1) prohibit voluntary prayer in public buildings; (2) lack procedures for the involvement of parents and representatives of the community in decisions relating to the establishment or continuation of religious studies; (3) limit parental visits to public schools or classes or the right of parents to inspect their children's school records; (4) require the payment of dues or fees as a condition of employment for teachers; or (5) lack procedures for parental review of textbooks prior to their use in the classroom. Stipulates that no Federal funds may be made available for curricula which promote values contradictory to the demonstrated beliefs of the community or for textbooks which tend to deny the role differences between the sexes.

Guarantees the right of any State or local educational agency to set qualifications for teachers, set attendance requirements for students, and to limit or prohibit the intermingling of sexes in sports or other school-related activities.

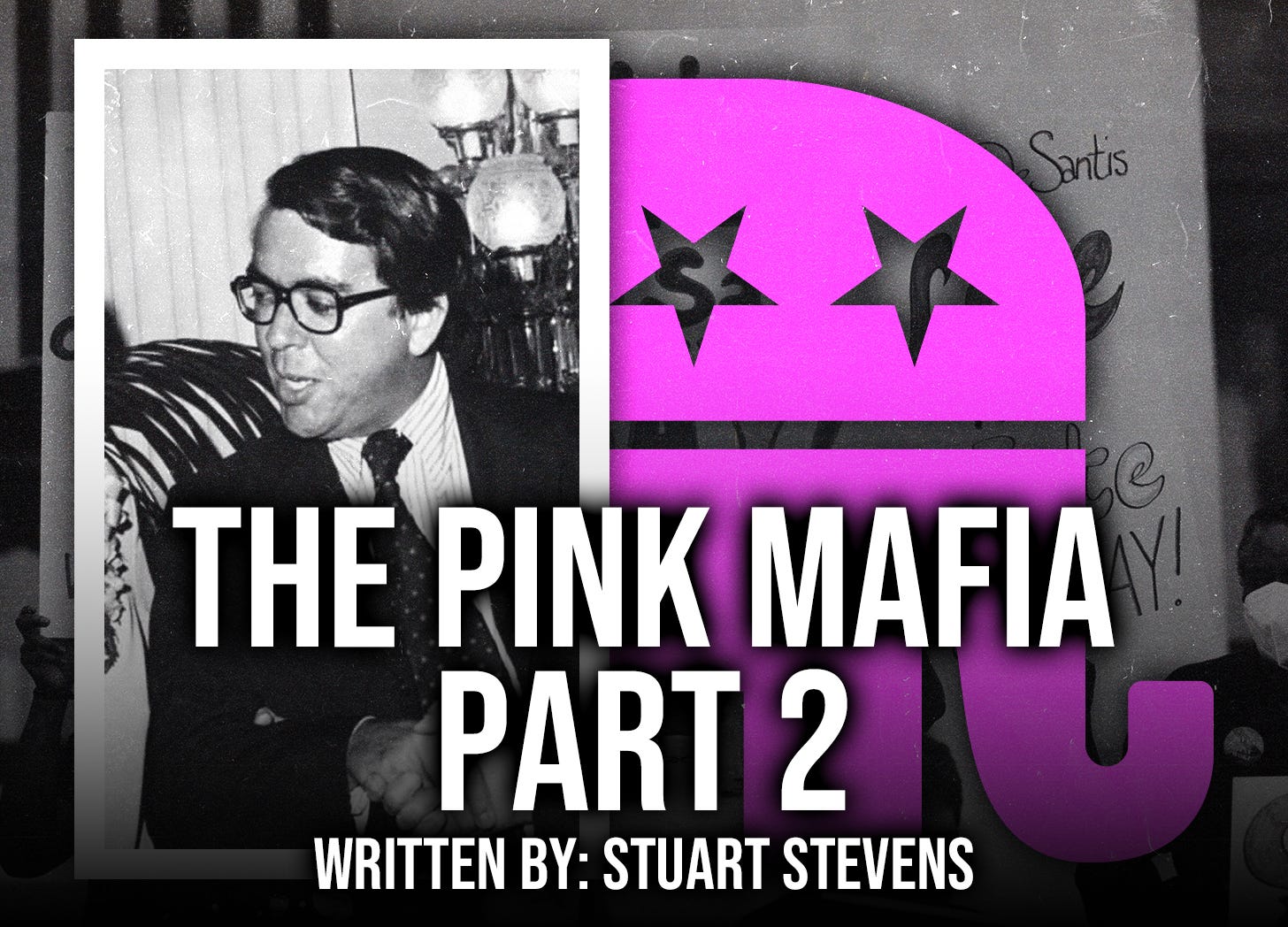

The bill had 19 co-sponsors, including Bob Bauman from Maryland’s First Congressional District, composed of the Eastern Shore and a few Baltimore suburbs. Bauman was elected in 1973 following the suicide of William Mills. (The First has a haunted modern history; more on that later.) When Jon Hinson was elected in 1978, my first dabbling in the dark arts of political media consulting, I went to work for him in his D.C. office. I can’t remember my title or even what my job description would have been. I do remember I was a terrible staffer who hated going to work in the Longworth Building and left after less than a year. And I do remember Bob Bauman.

He was a short bullet of a man who radiated a near-manic energy. “Each day, just before the House of Representatives convenes at noon, a dark-haired man takes up position near the Republican leadership table on the House floor within grabbing distance of a microphone and begins his afternoon’s vigil,” so opened a 1976 profile piece of Bauman in the New York Times. The Times was dedicating a profile to an obscure second-term Congressman from a district best known for Chesapeake Bay crabs because Bauman had defined his role in the House as a total pain in the ass.

“The 38-year-old Mr. Bauman has become the new gadfly of the House, its most active nit-picker, its hairshirt, its leading baiter of the most members,” the Times wrote. In real-world terms, that meant that Bauman was a self-appointed fiscal and moral watchdog of the House. He would force roll call votes to get all Members on the record and question any and everything the Democratic majority attempted to pass. He was hated by Democrats. House Speaker Tip O’Neil described Bauman’s approach as a “cheap, snarky, sly way to operate.”

Most Republicans found him annoying, if occasionally useful, as a way to throw sand in the gears of the Democratic Party that had held a majority since 1955. Bauman called those Republicans who objected to his tactics “Democrats in drag,” which, I suppose, would qualify as a classic Freudian slip. Jon Hinson, who had spent his life working as a staffer on Capitol Hill before his election in 1978, viewed Bauman as an eccentric crank, a distinct flavor in a world of mush. Both had been pages on the Hill at the same time and had a repertoire of amusing stories that revolved around parliamentary procedure. Several times, I joined them at the Monocle Restaurant for long, boozy dinners. At the time, I had no idea that Hinson was interested in men, and Bauman was still very much in the closet.

That closet was forced open on October 3rd, 1980, when Bauman was arraigned in D.C. Superior Court for soliciting sex from a 16-year-old male prostitute at the Chesapeake House in downtown DC. In his riveting 2022 book, “The Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington,” James Kirchick describes the scene of a typical night at the Chesapeake House.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lincoln Square Media to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.